When the sun sets on a giant, the shadows they cast are not of absence, but legacy. The passing of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, one of Africa’s most formidable literary figures, leaves a continent and a world reckoning with the void of his physical presence and the immensity of his intellectual and cultural inheritance.

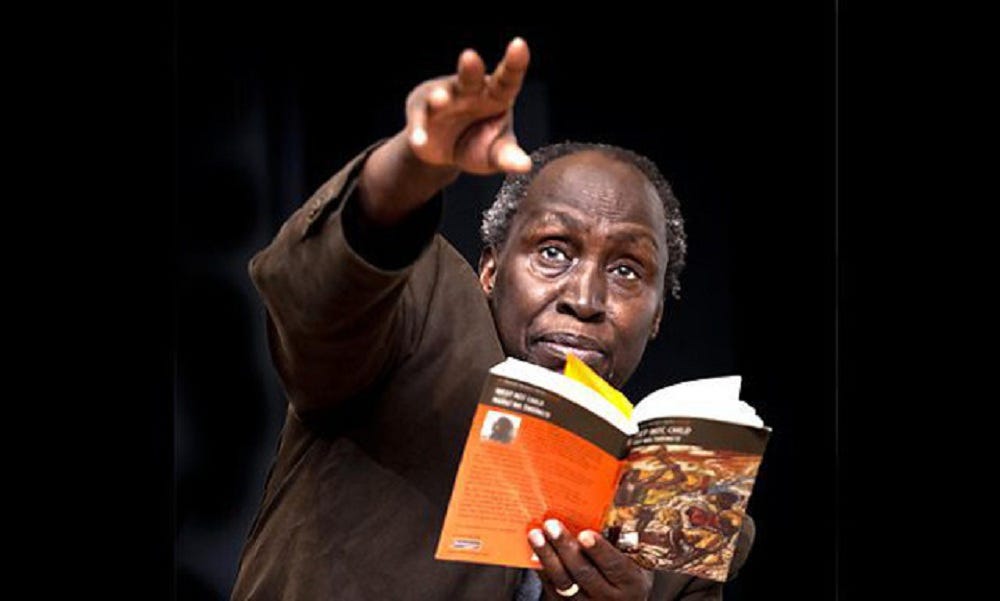

Born in 1938 in colonial Kenya, Ngũgĩ’s literary journey began in English, the language of the classroom, the church, and the coloniser. But what set him apart was not merely his talent, it was his defiance. He was not content to use the master’s tools; he sought to dismantle the house of colonial consciousness itself. This journey, from Weep Not, Child to Decolonising the Mind; charts a transformation from novelist to nationalist to radical thinker, and finally, to cultural prophet.

For those of us who walked the lecture halls of Makerere University, where Ngũgĩ once read and debated, his name rang not just with fame but with purpose. He reminded us that literature was not a decorative art but a weapon of liberation. He showed us that writing was not passive reflection but active resistance.

Ngũgĩ’s early works, especially The River Between and A Grain of Wheat, are foundational texts of postcolonial literature. They grapple with the trauma of colonisation, the ambiguity of nationalism, and the betrayal of post-independence ideals. But it is in Petals of Blood and later Devil on the Cross, that his vision sharpens into a critique of neocolonialism, capitalism, and the complicity of African elites.

Yet perhaps his most radical act was linguistic. Turning away from English to embrace Gikuyu, Ngũgĩ challenged the very framework of African literature. In doing so, he argued that true decolonisation cannot happen until African languages are given their rightful place in the intellectual and creative life of the continent. His essay collection, Decolonising the Mind, remains a seminal text in cultural studies and postcolonial theory.

Ngũgĩ’s life was not without hardship. He was imprisoned without trial for his political views, exiled for his critique of Kenya’s leadership, and blacklisted at home even as he was celebrated abroad. But even in adversity, he remained unbowed. His pen became sharper, his mind keener, and his vision clearer.

As a teacher and former literature student, I look back on his legacy with both gratitude and responsibility. Ngũgĩ taught us that literature must be rooted in the soil from which it grows. That our stories matter. That language is not just a medium but a memory, a worldview, a battleground.

In mourning Ngũgĩ, we are called to do more than remember him. We must read him. Teach him. Argue with him. Translate him. And most importantly, continue his work. Because for Ngũgĩ, the struggle was never just literary, it was human, cultural, and eternal.

Rest well, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. You gave us the tools. Now it is up to us to keep building the house of African letters.